A former hitchhiker’s introductory guide to the Chinese language galaxy

A former hitchhiker’s introductory guide to the Chinese language galaxy

About two years ago, my knowledge of the Chinese language, Mandarin, was limited to the dregs of Chinese culture that had made it west. I knew what “tai chi” and “yin and yang” referred to, but that was about it. I was happy about that.

As a traveller, I enjoyed going to foreign countries and immersing myself in the confusion and isolation that one can only get from being completely clueless to a language. As I grew older, I would realize that the most precious aspect of traveling is the relationships we form through sharing in conversation.

My wife Linzy, is fluent in both Mandarin and English and when discussing the subject of whether I should learn Mandarin with her, I confessed that the idea that I could learn Mandarin seemed unfathomable.

I explained to her that I’d been learning French since I was ten years old, on and off. Twenty years of learning French and although I am better than most, my French has much room for improvement. Given enough time I can read it; I can plough through Duolingo exercises with ease; I can speak it confidently in such a way I can navigate a restaurant and I can hear and understand it provided I have a patient speaking partner who responds well to “doucement s’il vous plaît” (slowly please).

I’m still not a fluent French speaker. Maybe if I moved there I would be. Maybe if I committed to 5 hours of classes a day, I could. It’s within reach. That said, it had taken twenty years to get to this point and in many ways it had been made easy.

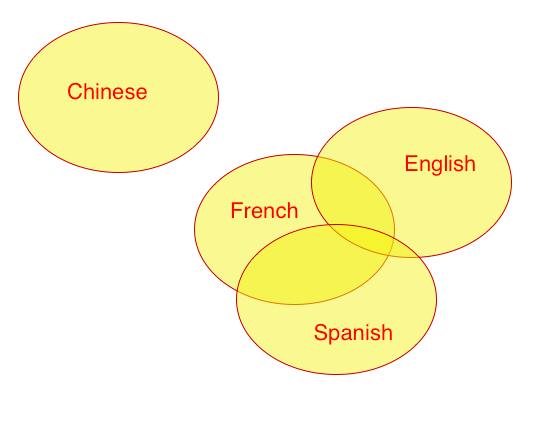

Romanized alphabet

French and English both share the Romanized alphabet. There are many words in French that are the same or similar in English. For instance, any English word that ends in “ion” is the same in French. Suddenly armed with the knowledge of a few basic words, you can say things like “J’ai (I have) un television et j’ai la information et j’ai ton (your) attention.” I’ve found these similarities helpful in other Latin based languages. I once had a productive conversation with an Italian where I spoke in broken French and she mixed broken English with Italian (which I do not speak) and I found despite the fact that we did not share a language, somehow we made that work. The human brain is awesome.

The latin based languages seemed achievable, Mandarin didn’t, I explained to Linzy. I drew a crude Venn diagram. Mandarin is so different. It shares nothing with my language. Mandarin words are nothing like English words. They look different. There’s no shortcuts. You have to learn everything from scratch. That’s overwhelming.

If I can’t learn French what chance do I have with Mandarin? My brain doesn’t work that way…

When needs must

Despite this, I wanted to learn how to speak Linzy’s native tongue. She has family members who I cannot speak to. There are times where Linzy will want to say something but the word does not exist in a language we both understand. We battle with cultural differences all the time and I believe if I could only learn her language, our relationship would grow richer and stronger.

Yet, despite the desire, the reality was overwhelming. I didn’t know where to begin.

The tonal system

I tell you this, not to put you off, but to give you hope.

As a speaker, who happens to know the Romanized alphabet and who wants to speak Mandarin, you need to learn Hanyu Pinyin.

Using a romanized alphabet, Pinyin condenses the pronunciation of the Mandarin language into words an English speaker can understand.

There are four intonations for a certain “spelling” of a word in Pinyin:

- qīng: (1st tone) with a level pitch e.g. 清 (clean)

- qíng: (2nd tone) with a rising pitch e.g. 情 (sentiments)

- qǐng: (3rd tone) falling and then quickly up e.g. 请 (please)

- qìng: (4th tone) with a descending sound e.g. 庆 (celebrate)

This is a very important part of Mandarin and difficult to grasp. It adds to the mountain of things to learn.

In September, during a trip to New York, Linzy and I attended the Comedy Cellar to see Hasan Minaj. However, what happened instead, was we fell in love with the ten minute warm up act — an Irish-American comedian known as Des Bishop.

He’d recently gone to China, learned Mandarin with the goal of performing standup comedy there. He succeeded and more.

I believe that in this small intimate venue, Linzy and I were the closest thing to Mandarin speakers, which I can attest to based on the fact that Linzy was laughing the loudest. Des explained in an extremely humorous fashion, how the 4 tones of Mandarin gave him some hardship in the early days, telling people his name was an unfortunate curse word beginning with “c” due to using the 1st tone (Bī) instead of the 4th (Bì).

Getting the tonal system wrong can have dire consequences, but despite this initial problem, Des made it work, as would I.

Speaking is hard

Even when the tonal system gets mastered, things can still go awry if the vowel sounds similar. One of my early conversations with Linzy began:

Linzy (in Mandarin): What did you eat?

Jon (in Mandarin): “Wǒ chī [fèn]”

Linzy (in English, laughing): You want to say “I ate rice”, yes?

Jon (in Mandarin): Yes.

Linzy: “Wǒ chī [fàn]”. Not “Wǒ chī [fèn]”. “Wǒ chī [fèn]” means “I eat 💩”.

Jon: 😯

At the face of this difficulty, I decided to break it down. I was going to focus exclusively on reading Mandarin from then on. Writing and listening and speaking would come later.

Linzy laughed.

“Isn’t that like learning half the language?”

“Well if I can learn Mandarin then I can read the signs in Chinatown… “ I explained… “I’ll be able to read food menus… I’ll be able to point at things and within time the listening and speaking will follow… I think?”

Linzy pointed out that the San Francisco Chinatown speaks Cantonese…

Cantonese

馬 => 马

Both of these words mean horse. The first is in traditional Chinese and the latter in simplified.

I had never really understood how Mandarin and Cantonese were related. I knew they were different things but I had always figured they were more or less the same. In my ignorance, I’d also come to the invalid conclusion that it was no different from a Yorkshire man speaking to a Londoner. I figured most of the words were the same. I was wrong.

I was to learn about the difference in character sets. Simplified as the name suggests simplified the traditional characters. Traditional is used in Cantonese and simplified in Mandarin.

With Linzy’s help I soon realised that many of the characters I’d been teaching myself were traditional, many were simplified and many belonged to both languages.

If Mandarin is scary. Cantonese is more scary. Not only do the words look more complicated to write, but when speaking Cantonese it involves 6 or 9 tones. At least Mandarin with its 4 tones was beginning to sound a little easier. A little more achievable. I could take comfort in the fact that I was not learning to read Cantonese.

Mandarin is poetic

My first breakthrough in learning to read in Mandarin, was realizing that certain characters have a poetry; a history; a beauty to them.

Some of the characters looked like the thing they represented, for example a mountain (山) or a person (人). The pictograms intrigued me in a similar way to how Egyptian hieroglyphics had in my childhood days.

A volcano (火山) is a fire (火) mountain (山).

To extinguish (灭) is to push down on a fire (火).

Some were more poetic and as a writer I found them beautiful to uncover, like reading a poem — a prisoner (囚) is a person (人) inside an enclosure (囗). Medicine (药), is an appointment (约) with grass (艹).

As I began to note these similarities, I found it interesting to think about how the language developed over time and how it reflected the culture.

A home (家) is a pig (豕) under a roof (宀). Did the Chinese use to keep pigs at home? A male (男) needs strength (力) to work in a field (田). Was this how men spent their days when the language was formed?

A watermelon (西瓜) is a western (西) melon (瓜), presumably because they were imported from the West. A trip to Wikipedia reinforced this, telling me that they originated in Southern Africa.

Beijing (北京) was the northern (北) capital (京). Nanjing (南京) was the southern (南). Did this mean Beijing was not always the capital?

I got obsessed with this and as a software engineer began to explore it in the form of a game. I found myself playing with the words, searching for patterns.

It was beautiful to explore, this language, and this early decision to learn to read was proving enjoyable. Not only was I memorizing a language, but I felt I was learning about a culture.

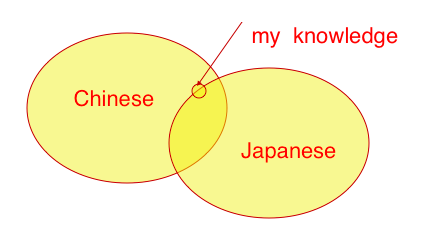

Chinese and Japanese languages overlap.

A volcano in Japanese Kanji, is also a fire mountain.

My new language may not have the similarities in Latin that I hoped for, but I was now realizing through my learning that I was unlocking much more, in cultures completely different from the one I grew up in.

Exit signs in Japantown and Chinatown were now more familiar (出). This was very motivating.

Mandarin is not always poetic

After time, I realized not every word made sense. Maybe, they did when they were written in traditional Chinese, but in the simplification process for some words, something had been lost.

Although (虽) is a combination of mouth (口) and insect (虫). A rainbow (虹) is an insect (虫) and work (工). An apricot (杏) is a tree (木) and a mouth (口).

Even though my attempts to put all words into categories and give them meaning was failing, I found this useful to help recall words. I could picture an army of worker ants building a rainbow…. I could picture a tree pooping apricots into a mouth. Although (虽) a fly (an insect 虫) had just flown into my mouth (口)… I would find a way to remember them.

American’s (美国人) can rejoice that they are seen as beautiful (美) country (国) people (人). Canadian’s (加拿大) will have to make do with finding ways to remember that their nationality involves the characters plus (加), take (拿) and big (大). Giant plus signs taking maple syrup?

Reading leads to speaking

Duolingo recently launched a Chinese app and I started to use it. I’m starting to speak limited Chinese now. My early adventures in reading Chinese feel like they are beginning to pay off.

One day, while trying to recall the word for “beautiful”, I remembered that American’s are the beautiful country people because I’d heard it spoken in the app and knew how to write the word.

I remembered it had three characters in it — 美国人 — and it sounded a little like how you say American in English — měi guó rén. With this knowledge, I was quickly able to deduce that měi was the first word — the beautiful word — the one I wanted to use — and the way my brain put that together was rather beautiful. Likewise, any time I found myself forgetting the word for big, I remembered it had something to do with CanaDa.

I found myself reaching for the sounds of words I had no idea I knew, such as Běi (north — 北) thanks to the mere knowledge of knowing the city Beijing (北京).

I was unlocking the language.

Conclusions in Singlish

The Duolingo Mandarin app, while limited in many ways, has been useful for learning how sentences are formed. As I’ve gone through the exercises, I feel like I am beginning to learn a lot about Singlish — the English creole language that Singaporeans — like Linzy — speak.

I’ve had to adapt how I speak around my extended family and I’ve noted that I communicate better when I drop all the surplus redundant words the English language likes to introduce. For instance, when speaking to my parent-in-laws I’ll now say “You eat already?” rather than “Have you eaten already this morning?”.

As I began to learn the structure of sentences, I note that the literal Mandarin for I have eaten already is “You eat already?”. I find this interesting, thinking about how Singapore — a country composed of many cultures — a country which counts 4 languages as official (English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil) — had to find ways that its 4 languages could communicate together.

The 4 languages of Singapore share little in common — Malay can be written in both an Arabic (Jawi) and Latin (Rumi) alphabet, while Tamil uses an ancient writing system called Vaṭṭeḻuttu. It’s amazing and not really a surprise that the English language, the only common language of these 4, adapted. How much of that had to do with the challenges, not too different from my own, of different backgrounds and writing systems colliding?

I still have a long way to go with my Mandarin adventure, but I’m starting to feel that I’ve created a path I feel comfortable walking. While I may be very far from fluent, I’m on a journey and anyone with even a slight hesitation of learning Mandarin should not be scared to join me.

On my journey, I note, that I am slowly but surely learning more about a language, more about a culture, more about a history and most importantly more about the woman I love.

I’m still learning, so please let me know in the comments, what hacks you are aware of and what mistakes I may have made in this article! I’d love to hear them!